Autor: Caroline Brown, Giorgio Iotti

Datum: 08.07.2022

Bei maschinell beatmeten Patienten treten häufig Asynchronien zwischen Patient und Beatmungsgerät auf (1, 2).

Die mangelnde Abstimmung zwischen den Inspirations- und Exspirationszeiten von Patient und Beatmungsgerät äussert sich in verschiedenen Formen, z. B. als verfrühte oder verspätete Einleitung der Exspiration, Autotriggerung, Doppel-Triggerung oder ineffektive Atembemühungen, und beeinträchtigt nachweislich die Behandlungsergebnisse (

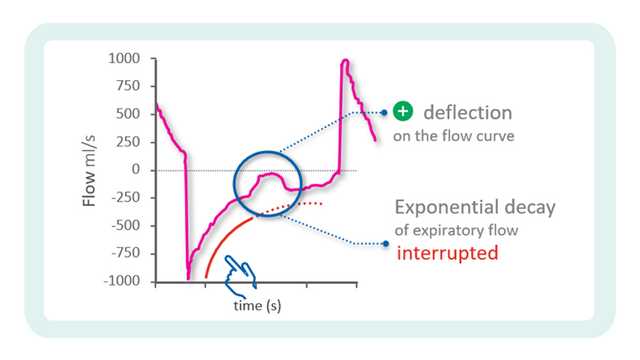

Das Konzept, zur Erkennung von Atembemühungen und ihres Timings die Druck- und Flowkurve im Atemweg zu analysieren, wurde das erste Mal bereits vor fast drei Jahrzehnten beschrieben (

Ein wichtiges Element bei dieser Studie war der Einsatz einer systematischen Methode für die Analyse der Druck- und Flowkurve im Atemweg. Diese umfasste fünf allgemeine physiologische Grundsätze und einen Satz spezifischer, vorab definierter Regeln („die Kurvenmethode“). Alle Patienten wurden mit einem Druckunterstützungsmodus beatmet und mit einem Ösophaguskatheter überwacht. Die Methode wurde auf die Druck- und Flowkurve im Atemweg angewendet, wobei die Werte mit einem proximalen Sensor ermittelt wurden. Als Referenz wurde der ösophageale Druck (Pes) herangezogen. Bei jedem Patienten analysierten drei Studienärzte aus einem vierköpfigen Team (drei Oberärzte und ein Assistenzarzt) ausschliesslich die Flow- und Druckkurven; der vierte Studienarzt wertete die Flow- und Druckkurven sowie die aufgezeichneten Pes-Werte aus. Die Atemhübe wurden als „normal“ unterstützt, automatisch getriggert, doppelt getriggert oder als ineffektive Atembemühung eingestuft. Bei den normal unterstützten Atemhüben wurden auch geringfügige Asynchronien (Triggerverzögerung, verfrühte oder verspätete Einleitung der Exspiration) beurteilt.

Der primäre Endpunkt war der Prozentsatz der spontanen Atembemühungen, die mit der Kurvenmethode ermittelt wurden. Zu den sekundären Endpunkten gehörten die Übereinstimmung zwischen der Kurven- und der Referenzmethode bei der Erkennung grösserer und geringfügiger Asynchronien sowie die Konkordanz der Beurteiler für die Kurvenmethode.

Insgesamt wurden 4.426 Atemhübe aufgezeichnet. Anhand der Pes-Referenzmessungen wurden 77,8 % davon als Atemhübe identifiziert, die korrekt vom Beatmungsgerät erkannt wurden, 22,1 % als ineffektive Atembemühungen und 0,1 % als automatisch getriggerte Atemhübe. Mit der Kurvenmethode konnten 99,5 % der spontanen Atembemühungen sowie alle automatisch getriggerten Atemhübe (bis auf einen) erkannt werden. Ebenso gab es eine sehr hohe Übereinstimmung zwischen der Referenz- und der Kurvenmethode bei der Erkennung von Atemhüben als unterstützt, automatisch/doppelt getriggert oder ineffektiv. Der Asynchronie-Index – die Summe der automatisch getriggerten, ineffektiven und doppelt getriggerten Atemhübe geteilt durch die Gesamtanzahl der Atemhübe – lag bei 5,9 %. Bei der Beurteilung mit der Kurvenmethode im Vergleich zum ösophagealen Druck gab es keine Unterschiede. Die gesamte Asynchroniezeit – die Zeit, in der das Beatmungsgerät und der Patient nicht synchron waren, geteilt durch die gesamte Aufzeichnungszeit – lag bei 22,4 %, wobei geringfügige Asynchronien 92,1 % ausmachten. Die Übereinstimmung unter den verschiedenen Beurteilern bei der Klassifizierung der Atemhübe war ebenfalls sehr hoch.

In über 90 % der Fälle konnten die Studienärzte Anfang und Ende der Atembemühungen mit ausreichender Genauigkeit ermitteln, sodass eine korrekt Erkennung der „geringfügigen“ Asynchronien – Triggerverzögerung, verfrühte oder verspätete Einleitung der Exspiration – ebenfalls möglich war.

Diese Studie liefert einige wichtige Erkenntnisse. Sie zeigt, dass es die Kurvenmethode dem klinischen Personal ermöglicht, einen extrem hohen Prozentsatz spontaner Atembemühungen zu erkennen und das Timing der Spontanaktivität von Patienten präzise zu beurteilen. Auch bei geringfügigen Asynchronien ist die Kurvenmethode sehr zuverlässig und wiederholbar. Die Bedeutung dieser Erkenntnisse wird durch ein weiteres Ergebnis dieser Studie unterstrichen, nämlich dass ein Grossteil der Asynchroniezeit bei der PSV mit geringfügigen Asynchronien verbunden war.

Diese Ergebnisse belegen nicht nur die Wiederholbarkeit der Kurvenmethode (hohe Konkordanz der Beurteiler); sie weisen auch darauf hin, dass die Schulung in der Kurvenanalyse nach einer vordefinierten, systematischen Methode eine entscheidende Rolle spielt. Es gibt Belege dafür, dass die klinische Erfahrung bei der Behandlung maschinell beatmeter Patienten nicht unbedingt mit der Fähigkeit einhergeht, Asynchronien zu erkennen; allgemein sind nur wenige Intensivärzte dazu in der Lage (

Die Autoren kommen zu dem Schluss, dass die Kurven für den proximal im Atemweg gemessenen Druck und Flow ausreichende Informationen liefern, um die Spontanaktivität des Patienten sowie die Interaktion zwischen Patient und Beatmungsgerät korrekt zu beurteilen – vorausgesetzt, es wird bei der Analyse eine angemessene systematische Methode wie die „Kurvenmethode“ angewendet.

Die IntelliSync®+-Technologie, die in den Beatmungsgeräten (

Den vollständigen Quellenverweis finden Sie unten: (

Unsere Übersichtskarte zu Asynchronien gibt Ihnen einen Überblick über die gängigsten Asynchronietypen, ihre Ursachen und wie Sie sie erkennen.

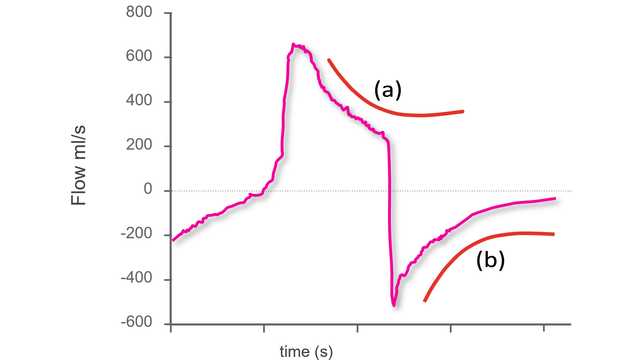

Um Asynchronien anhand der Standardkurven auf dem Beatmungsgerät erkennen zu können, müssen Sie zunächst wissen, wie ein synchroner Atemhub während der Beatmung mit Druckunterstützung aussieht.

In der vorherigen Ausgabe haben wir in unserem Tipp für die Arbeit am Patientenbett den Ausgangspunkt für die Identifizierung von Asynchronien anhand von Beatmungsgerätekurven behandelt.